One of my least favorite moments on watch is lying in my bunk knowing I’m supposed to be sleeping, but instead staring at the ceiling with just 40 minutes until I’m up on deck. On the other hand, when I’m standing watch, cold and exhausted, those same 40 minutes feel like a gift – like the sweetest countdown until I can finally rest. That’s offshore sailing.

Having a structure and a known rhythm takes the guesswork out of making it through the passage, and gives it form, a life of it’s own.

When you’ve got a steady breeze, comfortable seas, and the boat is moving sweetly along—it’s tempting to slip into a casual watch schedule. But when a cold front approaches, the wind rises, and the boat demands undivided attention, that’s when discipline pays off. Aboard Rocinante, we stick to our schedule no matter how calm things seem, because inevitably they will change. A rested crew is a prepared crew, and the structure trains your body into a rhythm so it’s ready to perform when it matters most.

It’s the steady heartbeat of a safe passage – a disciplined rhythm of observation, action, communication, and readiness.

My introduction to proper watch standing was aboard a 180’ square rigger with 20-plus crew. There was a constant hum of activity: adjusting sails, conducting boat-checks with a fifty item checklist, and endless maintenance. Even with seven on deck, watches were never dull. Just doing the dishes after a meal took a crew of three a solid thirty minutes. But the lessons from tall ships apply directly to passagemaking with a small team. One of the biggest takeaways was the thorough watch change—or turnover—routine. On the schooners and square riggers, it often took ten to twenty minutes. It wasn’t just a formality; it was the time for big maneuvers that needed more hands.

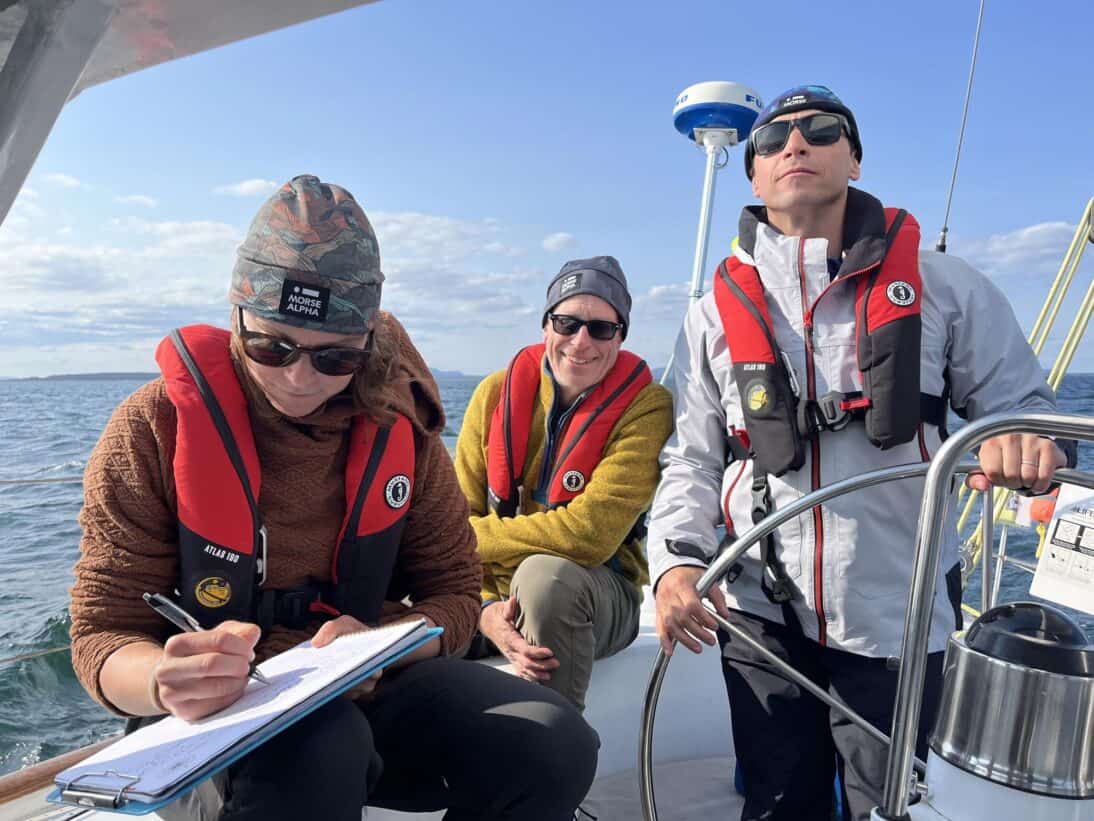

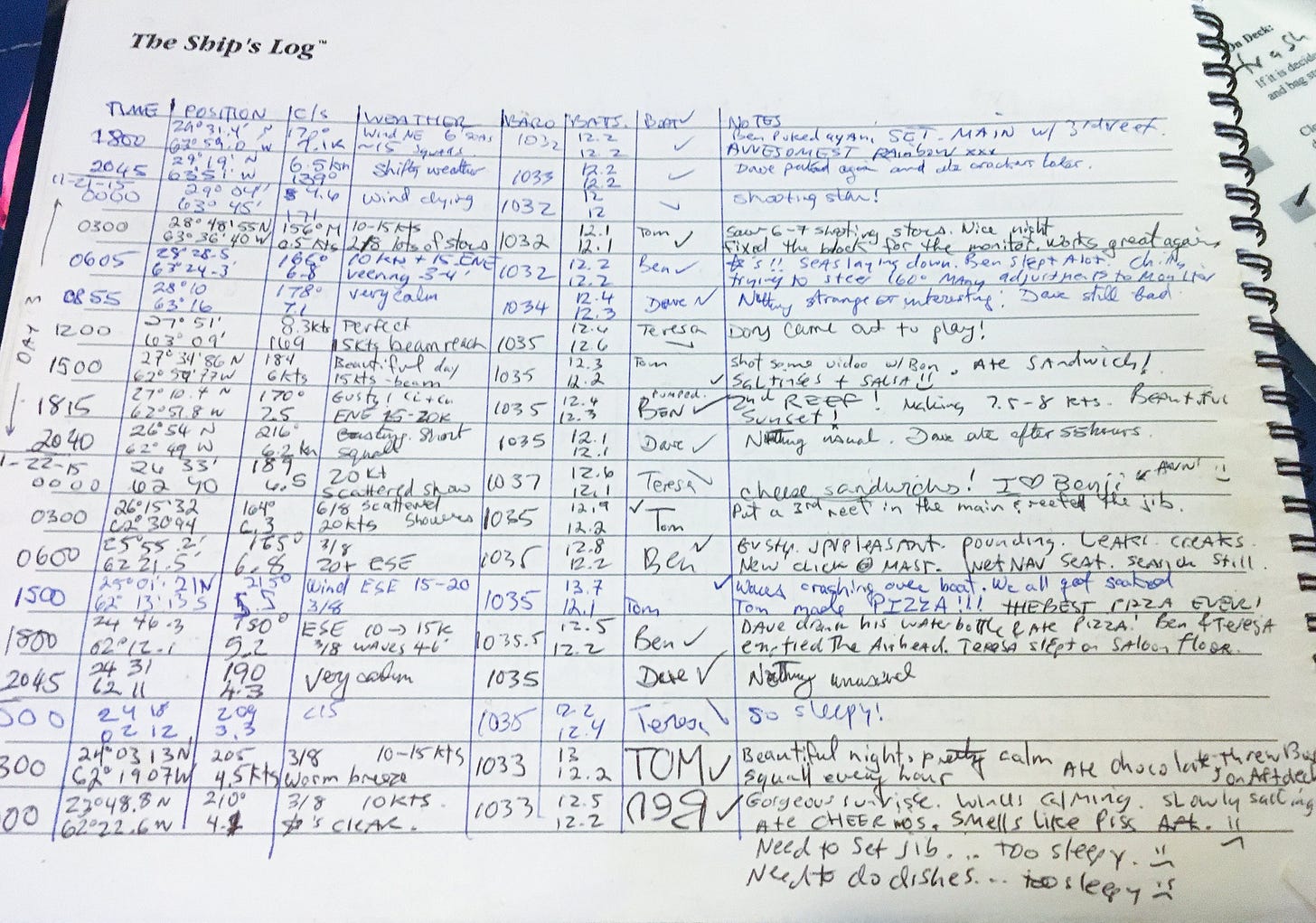

Aboard Rocinante, sail changes can take just one person, or up to three, so we use watch changes for those moments when needed. Once the work is done, the transfer begins in earnest. Having just completed our version of the “boat check,” outgoing crew pass along everything from the last three to six hours of sailing: observations, adjustments, ship traffic, wind shifts, bilge pumping, even small details like a flutter in the telltales, changes in sky cover, planet sightings, interesting smells, or which meals were eaten. These details might seem trivial, but offshore they’re often relevant. An increased frequency in bilge pumping could warn of a leak before it gets out of hand. Or a change in cloud cover can indicate an approaching front. And even what you had for dinner could matter eight hours later if someone ends up seasick—or worse.

The turnover is also when we talk through weather and sea state, review the passage plan, and confirm our progress. A handover might sound like: “We’ve traveled 36nm, on a course of 085º over the last five hours. The gusts were pushing us up, so I eased the mains’l to lighten the helm. If they keep building, we’ll put a reef in.” It is a brief but vital check-in, making sure everyone is working from the same shared mental model and ready for what’s next. Teresa always throws in, “We played twenty questions for two hours straight, and nobody’s beaten me yet!” I have to admit, her playful banter isn’t just for laughs—it keeps everyone sharp, engaged, and wide awake instead of half-asleep and zoning out.

Standing watch offshore is a blend of rhythm and readiness, making the passage feel like a timeless waltz of structure, discipline, and communication, but most importantly, trust in the routine.